Liberating Literacy: Power, Prison, and the Promise of Reading

Malcolm X’s biography famously details how he came to develop his literacy in prison by copying the dictionary:

I spent two days just riffling uncertainly through the dictionary's pages. I'd never realized so many words existed! I didn't know _which_ words I needed to learn. Finally, just to start some kind of action, I began copying…

With every succeeding page, I also learned of people and places and events from history. Actually the dictionary is like a miniature encyclopedia. Finally the dictionary's A section had filled a whole tablet-and I went on into the B's…

I suppose it was inevitable that as my word-base broadened, I could for the first time pick up a book and read and now begin to understand what the book was saying. Anyone who has read a great deal can imagine the new world that opened. Let me tell you something: from then until I left that prison, in every free moment I had, if I was not reading in the library, I was reading on my bunk. (114)

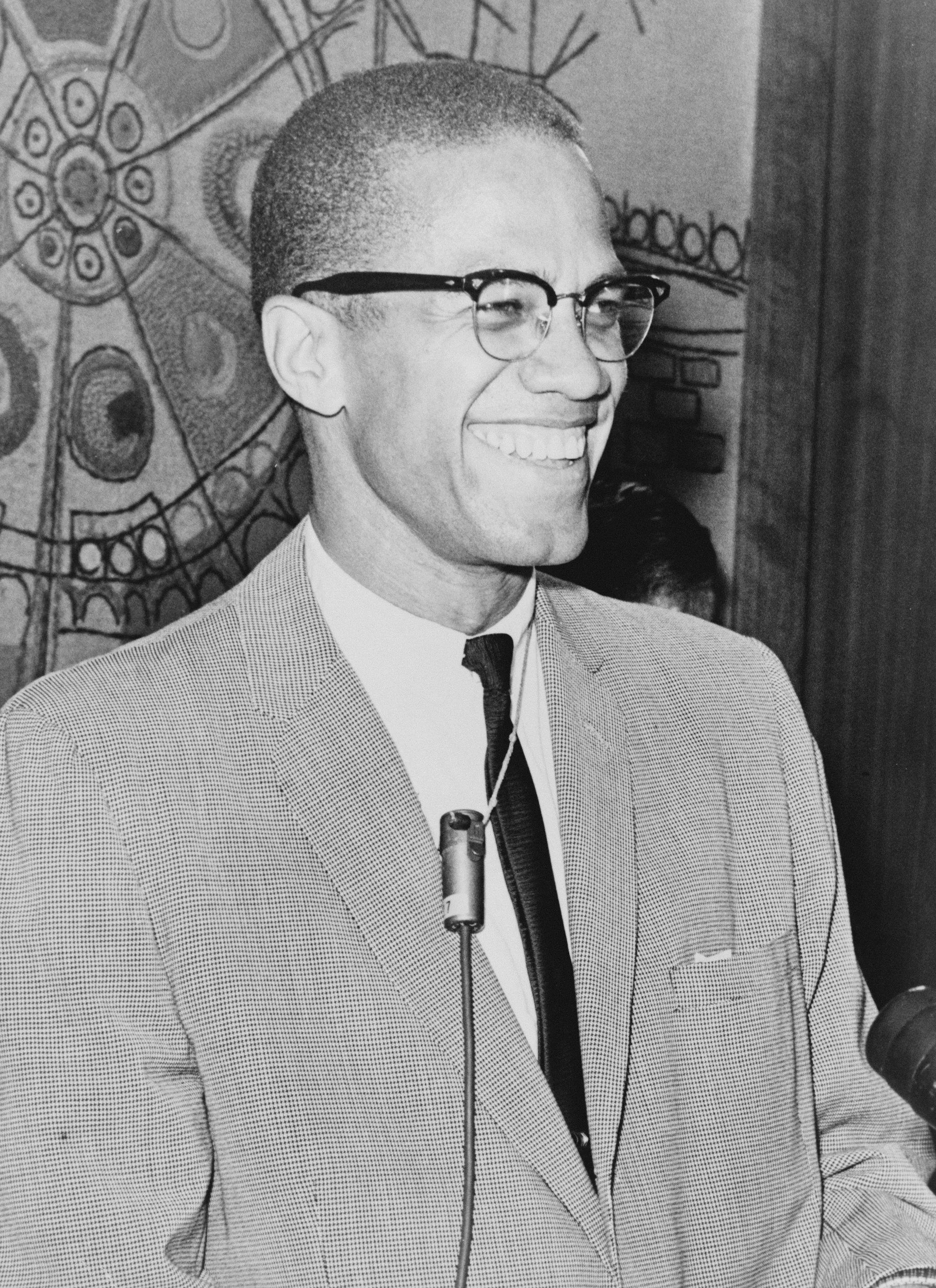

Malcolm X’s biography famously details how he came to develop his literacy in prison by copying the dictionary. Source: Library of Congress

The Scope of the Literacy Gap

X’s desire to increase his literacy is not uncommon. Two thirds of incarcerated people–even with a high school diploma–have below the minimum literacy skills necessary for workplace competence. People know that literacy is a skill that will benefit them.

This is why literacy support is crucial for the Petey Greene Program. One-on-one tutors support literacy through reading along and with students. College Bridge courses help students further develop their literacy skills through class conversations and writing about texts. We are also working on developing direct literacy instruction. We know literacy is an essential skill.

Literacy is correlated with everything from longer lifespans to greater autonomy and personal fulfillment, and is necessary for employment and navigating the basics of life from renting housing to applying for credit. It also helps people to make sense of the world and our place in it—as it did for X. Literacy empowers in more than practical ways. It’s one of the greatest assets a person can have.

Literacy as Control in Prisons

Yet, we also know that the way reading is taught matters profoundly. In the history of prisons, literacy has been a tool for carceral paternalism to impose a certain moral order. Early penitentiaries permitted imprisoned people to read only the Bible, prayer books, and religious tracts. As Megan Sweeney (2010) notes, in Reading Is My Window, this practice persisted through the secular “bibliotherapy” in the twentieth century and continues to inform carceral censorship practices today. In his opinion on Beard v. Banks–a landmark First Amendment in prison case–in 2006, Justice Clarence Thomas cited the eighteenth-century Pennsylvania practice of allowing imprisoned people to read only the Bible as precedent for denying access to secular newspapers.

Sweeney draws on Eva Illouz’s (2008) Saving the Modern Soul: Therapy, Emotions, and the Culture of Self-Help to suggest that this history has, in the 21st century, morphed into explanations on the benefits of reading and literacy that extol its therapeutic and expressive possibilities. It’s essential, in teaching literacy and talking about the power of literacy, that we not fall into this moralizing trap—presenting evidence in a way that makes it seem like literacy is all that’s needed and inadvertently shoring up the penal system itself by implying that such self-improvement can be done effectively in a carceral setting.

While literacy is correlated with longer lifespans, higher earnings and stronger marriages, it can’t be treated as the sole determinant of economic or social success (Graff). We know that people need other kinds of support—like fair hiring practices and affordable housing. But literacy helps empower people to identify resources, gives them the confidence to ask questions and pursue options.

Literacy Is Social, Cultural, and Relational

Despite literacy’s benefits, it’s widely unavailable or under-resourced in prisons. A 2016 Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) report found that “twenty percent of incarcerated adults who did not want to enroll in academic programs indicated that the academic programs at their facilities were either not useful or were of poor quality.” This perception is not inaccurate. A recent quantitative study, “Investigating prison factors related to literacy and numeracy skills of incarcerated adults” (2024), found that participation in reading, writing, or numeracy activities while imprisoned did not lead to consistently higher scores on the PIAAC literacy or numeracy assessments. Most prison systems, including federal prisons, count GED classes as literacy instruction. These classes focus on teaching to the test and instructors are overwhelmingly not trained on literacy instruction, particularly for adults. This drill-and-kill method doesn’t result in real comprehension, in part because literacy is a culturally embedded and socially constructed practice.

Comprehension relies on references to other texts, understanding history and being able to parse a writer’s position and intentions, even when indirectly stated. When literacy instruction is predicated on information outside the learner’s knowledge, it is further complicated and impeded. Harvey Graff’s (1979) The Literacy Myth reminds readers that “there is no single road to developing literacy”; literacy acquisition varies widely based on context as well as individual motivations and resources. Reading is a social, not merely technical skill. Literacy is best developed by reading texts of interest and accessible to the reader, and then discussed with others. In helping incarcerated and systems-impacted people acquire better literacy skills, it’s essential to understand these complexities to meet people where they are and to ensure that people can take ownership of their learning, self-determining what reading they want to pursue.

A Non-Moralizing Approach to Literacy

Literacy is a tool for self-determination—enabling the pursuit of dreams, the fulfillment of needs and establishing and maintaining connections to others. In the isolation of prison, and without literacy, people are completely alone. But, in advocating for literacy, it’s essential not to fall into the moralizing trap. For example, Cavallaro’s 2019 study of prison education programs found that 61% of programs cited statistics showing that their students’ recidivism rate was lower than the national average. While literacy does help people navigate life in our society, recidivism is not the sole result of personal decisions or capabilities. Recidivism is perpetuated by onerous parole requirements, exclusion from housing and employment due to criminal records and a host of other socially determined policies that demand to be addressed. Finlay and Bates (2018) argue in “What is the Role of the Prison Library?”, the criminal justice system’s promotion of education as a “mechanism to reduce reoffending” encourages prisoners to view it as just another method of reform, exacerbating the negative view of schooling held by many incarcerated people.

But literacy when given to incarcerated people through high-quality instruction that is non-moralizing and empowers them to make their own learning path is one of the most powerful tools a person can be provided. Literacy and writing allow incarcerated Black students to create what the ethicist Hilde Lindemann (2001) calls “counterstories” in Damaged Identities, Narrative Repair. They also grant access to what Kirkland and Jackson (2009) refer to as the “individual potential for social and cultural critique” and a “tool for participating in culturally valued experiences.” McKinney and Hogan suggest that discussing difference in dialect and expression are helpful for learners to understand the dynamism of language. Literary analysis focused on vernacular texts (as described in Franklin and Sweeney’s accounts of teaching urban fiction) can also facilitate students’ fluency.

If you’re interested in supporting the Petey Greene Program’s literacy work through volunteering or a donation please get in touch.

The Petey Greene Program offers literacy instruction to system-impacted people that acknowledges literacy is not value-neutral. We do this by educating our volunteers on the history of literacy. Our instructors teach texts that are representative of diverse perspectives and lived experiences. The goal is to assist our system-impacted students who have been excluded from the benefits literacy provides, while also affirming that literacy deficits are not the result of individual failure and their comprehension challenges are, in part, related to culturally narrow instruction that often excludes references and context that would facilitate their understanding.

The Petey Greene Program has a variety of literacy support, from one-on-one tutoring to our College Bridge program which helps students elevate their literacy for college coursework, to our direct literacy instruction, currently in development.

Bibliography

Aldib, Roula, Lee Branum-Martin, Şeyda Özçalışkan, and Rose Sevcik. “Investigating Prison Factors Related to Literacy and Numeracy Skills of Incarcerated Adults.” Zeitschrift Für Weiterbildungsforschung, October 4, 2024.

Berry, Patrick W. “Doing Time with Literacy Narratives.” Pedagogy 14, no. 1 (January 1, 2014): 137–60.

Brandt, Deborah. Literacy and Learning: Reflections on Writing, Reading, and Society. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009.

Cavallaro, Alexandra. “Making Citizens Behind Bars (and the Stories We Tell About It): Queering Approaches to Prison Literacy Programs.” Literacy in Composition Studies 7, no. 1 (March 14, 2019): 1–21.

Coles, Justin A., Roberto Santigo De Roock, Hui-Ling Sunshine Malone, and Adam D. Musser. “Critical Literacy and Abolition.” In The Handbook of Critical Literacies, edited by Jessica Zacher Pandya, Raúl Alberto Mora, Jennifer Helen Alford, Noah Asher Golden, and Roberto Santiago De Roock, 363–72. New York: Routledge, 2021.

Finlay, Jayne, and Jessica Bates. “What Is the Role of the Prison Library? The Development of a Theoretical Foundation.” Journal of Prison Education Reentry. Vol. 5, 2019, No. 2 (2018).

Fish, Stanley. “What Should Colleges Teach? Part 3.” The New York Times (7 September 2009).

Franklin, H. Bruce. “Can the Penitentiary Teach the Academy How to Read?” PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 123, no. 3 (May 2008): 643–50.

Graff, Harvey. The Literacy Myth: Literacy and Social Structure in the Nineteenth-Century City. Cambridge: The Academic Press, 1979.

Graff, Harvey. “The Literacy Myth at Thirty.” In Journal of Social History 43 no. 3 (2010), 635–661.

Heiner, Brady T., and Sarah K. Tyson.“Feminism and the Carceral State: Gender-Responsive Justice, Community Accountability, and the Epistemology of Antiviolence.” Feminist Philosophy Quarterly 3 no. 1 (2017).

Illouz, Eva. Saving the Modern Soul: Therapy, Emotions, and the Culture of Self-Help. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

Kirkland, David E., and Austin Jackson. “‘We Real Cool’: Toward a Theory of Black Masculine Literacies.” Reading Research Quarterly 44, no. 3 (July 9, 2009): 278–97.

Lindemann, Hilde. Damaged Identities, Narrative Repair. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

McKinney, Emry, and Chad Hoggan. “Language, Identity, & Social Equity: Educational Responses to Dialect Hegemony.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 41, no. 3 (May 4, 2022): 382–94.

Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). “Highlights from the U.S. PIAAC Survey of Incarcerated Adults: Their Skills, Work Experience, Education, and Training.” 2016.

Rodríguez, Dylan. Forced Passages: Imprisoned Radical Intellectuals and the U.S. Prison Regime. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Rolston, Simon. Prison Life Writing: Conversion and the Literary Roots of the U.S. Prison System. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2021.

Schaffer, Kay, and Sidonie Smith. Human Rights and Narrated Lives. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

Street, Brian V., and Stephen May (eds.). Encyclopedia of Language and Education: Literacies and Language Education. New York: Springer, 2017.

Sweeney, Megan. Reading Is My Window: Books and the Art of Reading in Women’s Prisons. Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

“This Ain’t Another Statement! This is a DEMAND for Black Linguistic Justice!” Conference on College Composition and Communication (July 2020). https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/demand-for-black-linguistic-justice.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti. 2010. “Should Writers Use They Own English?” Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies 12 (1): 110–17.

Research support for this article was provided by Eli Hardwig.